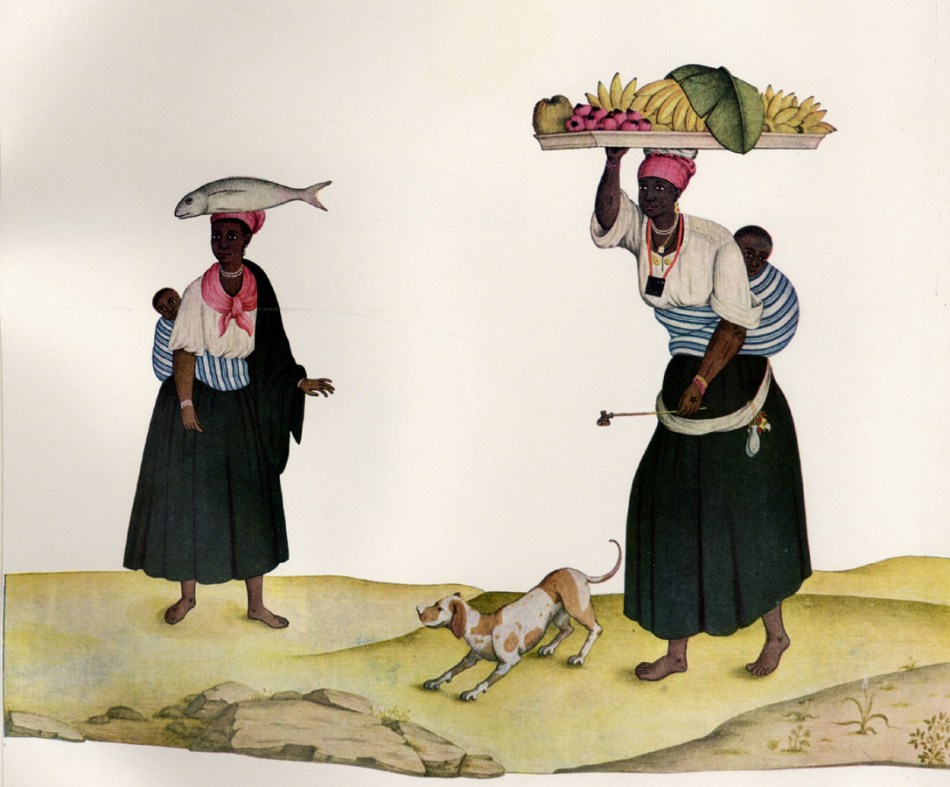

All historic images were sourced from www.slaveryimages.org, compiled by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite, and sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library.

WHEN I was about eleven or twelve years old my grandfather gave me a book that inspired me to see the world in a broader context. The book was called The Masters and the Slaves, or its original title: Casa-Grande & Senzala.

Gilberto Freye was Brazil’s foremost cultural historian-sociologist. The paperback book my Grandfather gave me was well worn by the time I put my hands on it. It was a thick tome, describing a world very familiar but exotic–a world build on Native American, African and European cultures thrust together in the Atlantic world. It was published in 1932 and was perhaps his most famous study of the development of Brazilian civilization.

The last two chapters of the book, rich in material and quite raw in truth were called “The Negro Slave,” the second of the two delved fully into the food culture of enslaved of Brazil, focusing mostly on northeast Brazil and Amazonia and Rio De Janeiro where the enslavement of Africans in Brazil was particularly dense and essential to the rice, sugar, coffee, cotton and tobacco plantations as well as the mines and the construction of roads and cities and the casas grandes–the Big Houses–that held rule over thousands of Africans. Brazil imported more enslaved Africans than any other location in the New World. It swallowed many of their bodies whole–most did not live 7-10 years beyond their arrival if that.

A device used to punish Brazilian enslaved for stealing food, ingesting dirt or intoxication. A metal mask…

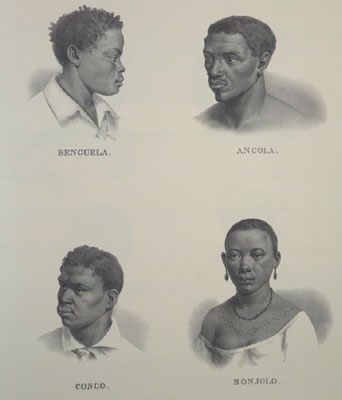

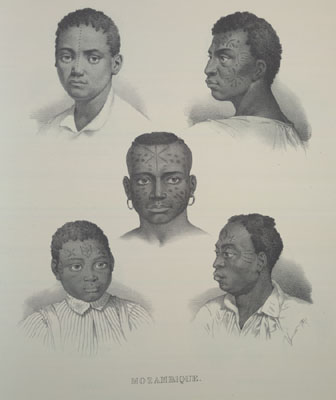

Between 1502 and 1866–5.5 millions left on ships from West, Central and Southeastern Africa and under 4.9 million arrived alive. Rio and Salvador Da Bahia were two of the New World’s largest slave ports, with arrivals dwarfing anything seen in North America and the Caribbean. Slavery in Brazil began in the 16th century and ended in 1888–a full twenty-three years after the end of the Civil War in the United States.

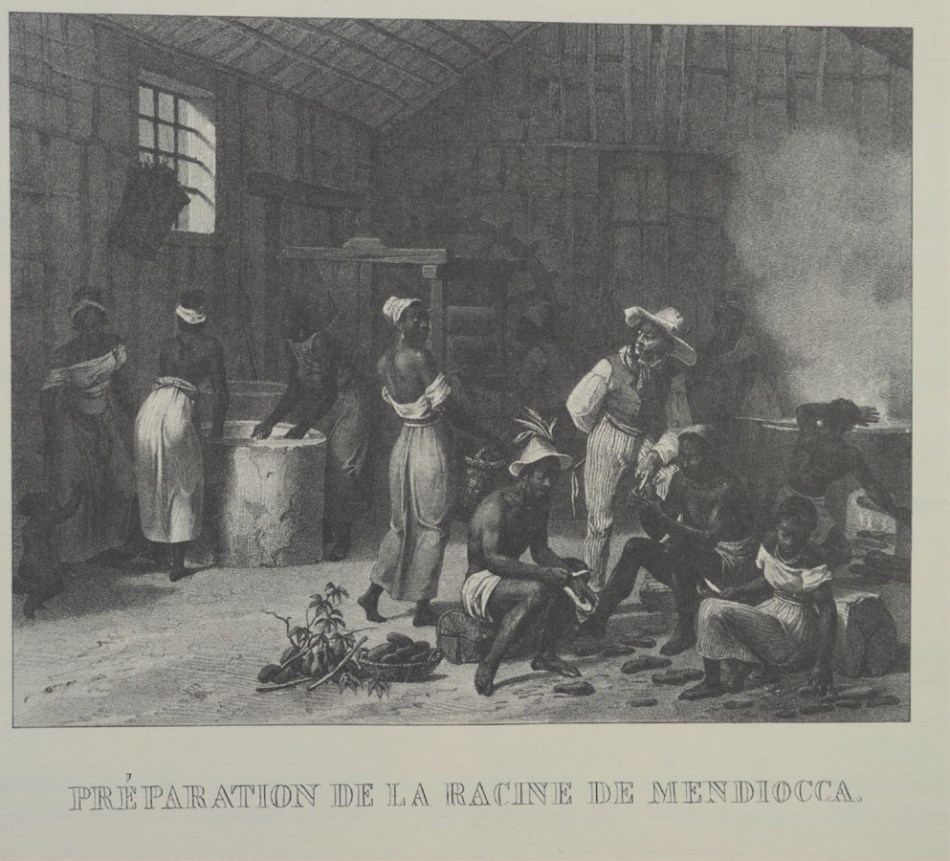

Enslaved Brazilians preparing Cassava/Manioc.

So I was 12 I didn’t have the internet to tell me anything about Africans in Brazil. But this book-a few years shy younger than my maternal grandfather—told me about family further down the Atlantic coast. Now, looking back, knowing I have genetic cousins in Brazil, among other places in the Black New World; knowing that some of my blood came to North America and some went to South America –it makes the connection to Black Brazil that much more emotional, strong, and yes in some ways painful and bewildering. However this Brazilian scholar–definitely proud of the contribution of Africans to the lifeblood of his country–gave the grandest account of the African origins to the Brazilian palate.

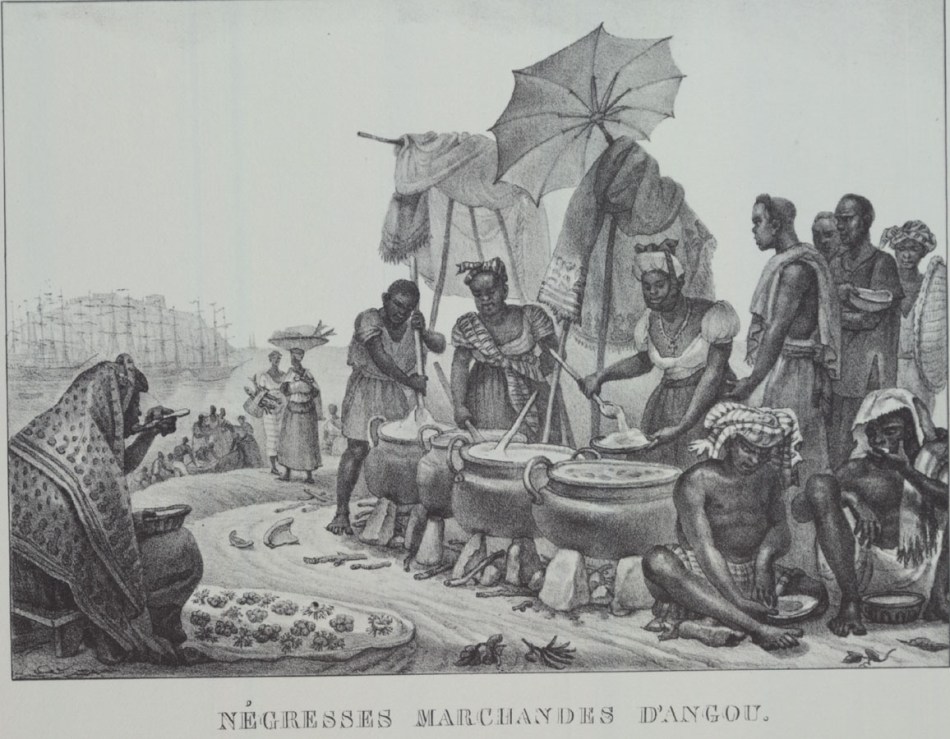

Angou–corn, Cassava or rice porridge sold at market.

Freyre’s version of Brazilian civilization the importance of the enslaved African to the Brazilian kitchen was crystal clear: “There is one important aspect of the Brazilian that remains to be stressed, and that is the culnary aspect. The African slave dominated the colonial kitchen, enriching it with new flavors.”

To Gilberto Freyre, the culinary heritage of Brazil was inseparable from the cuisines of other parts of the New World–he studied in Texas and traveled throughout the American South–including South Carolina and New Orleans, describing a South Carolina estate as “a real Northern Brazilian plantation manor..with the best kitchen in the environs of Columbia. In New Orleans also, I tasted sweets and confections with the pleasing flavor of Africa, putting me in mind of those of Bahia and Pernambuco. Especially the dishes prepared from chicken with rice and okra.” It was telling he described the two parts of Brazil most affected by West African culture–especially that of Senegambia and the Slave Coast. “The genius involved was that of the African slave woman rather than that of the the white mistress.”

Market women

Freyre was keen to speak honestly about what he saw as elements of Brazilian kitchen culture. The Afro-Brazilian impact was felt in the markets, the Big House kitchen, the taverns of the cities, from the cultivation of the ground and harvesting of the sea and rivers to the settlements of maroons in the rainforest–some were even independent states nearly lasting a century. Their food was tied to their other major contributions–music, religion–Candomble and Umbanda–and language. “The slaves employed in the Big Houses had highly specialized functions, and two or sometimes three of them were always reserved for work in the kitchen. Ordinarily these were enormous black women, but occasionally they were male Negroes who were unsuited for hard labor but who were without rival in the preparation of culinary sweets and confections. These later were always very effiminate…They were the greatest chefs of colonial times, as they still are today.” Freyre recognized there were gay enslaved people and yes, Virginia, they played a role in shaping the foodways of his nation.

Vatapa (Wikipedia)

If you don’t know Brazilian food–its an amazing amalgam of Portuguese, Tupi, Tupuia, Gurani, and other Native American traditions, and the traditions of the Manding, the Wolof, the Balanta, the Manjac, the Bubi, the Yoruba, the Fon, the Akan, the Kongo, Kimbundu, Yao and Makua. From this mixture came the national dish feijoada–a bean dish from Portugal with African flavors and trappings–and the main condiment–melegueta pepper—actually not the West African melegueta–but bird chilies that season everything. Okra, black eyed peas, pigeon peas, hot peppers, rice, tomatoes, spare parts of the pig, fresh seafood, piquant sauces, leafy greens, sesame, collard greens, tropical fruits and sugar cane–and the ubiquitous dende oil–palm oil–defined the African relationship to Brazilian food.

Acarajé (Wikipedia)

Freyre’s Bahia, Rio and Pernambuco were the old Brazil…a place not dissimilar to the pre-emancipation Caribbean or the old South. The streets of Brazil smelled of rice pudding, fried fish, roasting ears of corn, calves and pigs feet, sweet corncakes, sugarcane rolls, collard greens, bits of slow roasted snd heavily spices meat, couscous, popcorn, okra stews, ginger, garlic, fiery hot chili sauces, peanuts with cumarí and pé de mulceque–a peanut candy literally named “foot of a Negro boy.” Sound familiar?

Africa provided dendê oil–from ndende–the orange palm oil–the basis of deep frying and sauté for stews, maxixé–the burr gherkin, acarajé the black eyed pea fritter, caruru–the Brazilian answer to callalloo and vatapá a popular dish made with coconut milk, palm oil, shrimp, and hot peppers, and they preserved acaça, balls of pounded dough eaten with stew from Dahomey and cuxa, a leafy green sauce from Senegal. These African hallmarks merged with Native Brazilian fruits, nuts, fish and game merged with Portuguese standards like caldo verde and feijao and the olive oils and wines of the mother country. The Afro-Islamic influence of the Moors–with their spices, sweetmeats, and other elements of Northwest Africa and the Arab world complicated this cuisine. Many Jews and Moriscos–Muslim converts fled to Brazil in the early years of the colony to escape the Inquisition. Many of the foods beloved by Brazilians were directly tied to the worship of the Orixa–the deities of the Yoruba traditional religion. Feijoada is associated with Ogun, acarajé with Iyansan/Oya, popcorn with Omolu, acaça and cachaça with Exu, and fresh with Yemoja.

I encourage you to read The Masters and The Slaves. Freyre was not without his faults or controversies but this book did something no work of serious scholarship did about American slavery until recent years. I hope to continue his legacy and bring greater awareness to the heritage of Africans in the United States and honor my blood cousins in Brazil. I cannot believe how important this small book has impacted me. I say obrigado, to my grandfather and old ones (the pretos velhos)for their guidance. AXÉ!!

Dedicated to judoka Rafaela Silva–congratulations on your gold medal at the Rio Olympics 2016-the Egun are so proud of you!! As so are all of us!

Don’t forget to vote Afroculinaria for Best Food and Culture blog on Saveur!

Thank you for the education.

LikeLike

It’s always a pleasure to read your blog, you are so informative and pertinant.

LikeLike

Thank you for the book recommendation. Your post was fascinating and extremely revealing.

LikeLike

Your blog is so great and informational!

LikeLike

Pingback: Afro-Brazilian Cuisine: A Search for the Roots of Soul Food

wonderful illustrations, thank you.

in cuba, it is argued that the catholic church in the 1789 Codigo Negro Espanol, protected slave marriage and forbad the children from being sold, which helped preserve the yoruba language, still spoken in cuba, and its syncretized religion, santeria. (slave owners didn’t always cooperate.) it is alleged the Codigo Negro also ameliorated slightly the cane cutting conditions in cuba. finally, it is alleged cane-cutting conditions in brazil were much, much worse, with enslaved people cutting cane from [horse drawn? slave-drawn?] cages. i am interested in the disparities and look forward to all you got to offer on cuba/brazil slaveries.

finally, as a marylander, i wonder if “pounded dough” for dahomeyan stew is the forefather of maryland beaten biscuits?

LikeLike

Pingback: article: How a Brazilian Scholar Inspired My Search for the Roots of Soul Food – nbx.report