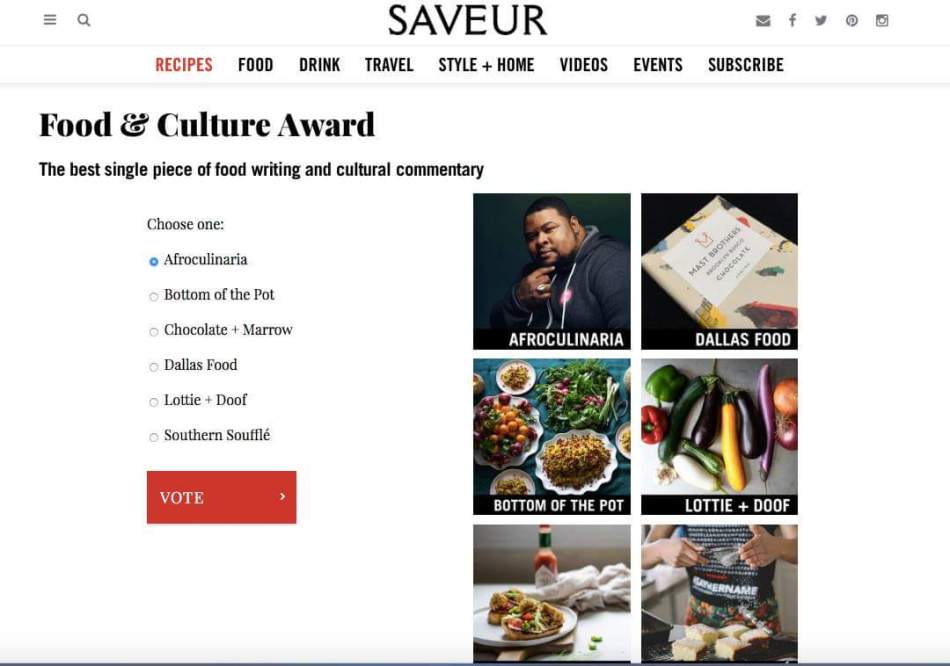

Nominated by Saveur!

3000 plus words—turn back now or read until the end…grab coffee now.

I have to have a conversation with chef Sean Brock. Sean, I hope you’re reading this. Immediately. Things have gotten out of hand in the discourse on “race” and Southern food and it’s time we hashed things out. One to one, personally, and have a hummus summit. (warning: satirical Israel/Palestine peace process reference) It doesn’t matter who made the hummus first or who made it better, or whose hummus is more authentic; the point is we both make hummus, we both love hummus and we want people to appreciate what hummus means to us and we want people to keep making hummus, secure in the knowledge that hummus is a part of everyone’s story and that hummus will endure.

But we are not talking about hummus—we’re talking Southern food—and specifically we’re talking Lowcountry food and what Charleston brings to the table—we are talking power, access, and moving the conversation beyond triggers like “culinary appropriation,” into discussions of culinary justice, amplification, and social and political responsibility.

This is serious shite. We are long overdue for a summit Mr. Brock.

The past 24 hours have changed me. I can’t say for the better. Those who know me and my work know that I strive to choose a higher path—I am happy to be bound by Jewish law to look inside myself and weigh and judge my actions, thoughts and choices. G-d or no G-d, and maybe it doesn’t matter, I have a charge to keep and I find it difficult when the challenges to my identity, my work and my integrity force me to fight back and give retort. I should note with just a bit of irony the word for “war,” (milchama) and the word for “bread,” (lechem) in Hebrew share the same root (lchm). Bread—coded down to us from the days of old as both money and the basis sustenance—food—is often the place where conflicts begin and end.

This I will concede—and I may concede nothing else—you and your fellow chefs have the right to “do you,” however you please. You can cook whatever you want, call it whatever you want, stand tall in your convictions and communicate the message you want on your own terms and charge what you will for the experience. It is not my prerogative to circumscribe your potential or curtail your growth or trajectory. My advocacy was but a whisper once upon a time and I could be easily ignored but now it has gained traction and perhaps now you will incline your ear and listen to what I have to say—as an equal with my own place at the table—earned in cuttings of cane, burns, cuts, pounds of cotton and hands of tobacco and sowings of rice. I have stirred the pot, putting myself in the footsteps of those many of your leaders do acknowledge and do write about—even if I wonder to what end. The research, recreation and interpretation of enslaved people’s food is not personally or communally easy—and it goes beyond creativity and taste—it is in many ways a willed descent into hell. I assure you it is taxing, painful and revelatory—but I have no choice—as you have no choice but to be who I was created to be.

But like my spiritual Ancestor, Esther ha-Malkah, I come on this day, the 13th of the moon-time of Adar in the year 5776 to plead for myself and for my people. My people are the living and the dead—and unfortunately, the dying. In 2006 I touched the saltwater at Sullivan’s Island for the first time. It was my first engagement with the place that many have called “The Ellis Island of Black America.” I was corrected by Marquetta Goodwine, “Queen Quet,” to many that no—this was no Ellis Island. Despite the fact that roughly the same number of European immigrants had come through Ellis in relation to enslaved Africans who came through the port of Charleston—roughly 40ish percent…that’s abstractly 4 out of every African Americans who can trace an ancestor back to that one spot—these were enslaved people, not people looking for a better life.

It was at that moment, ten years ago I sank to my knees in the wet sand, fully clothed and guaranteeing my jeans would be stained—and humbled myself before my dead. At the time I did not know where they came from or who was there—I just knew this was where I had to start. You know Sullivan’s Island—its bordered by condominiums and would be nothing if the Revolutionary War and Civil War had not left their marks there. Even though this space is as important as any Charleston antebellum mansion—piazza and all—its not a million dollar space—its just a plaque and a bench lovingly donated by nobel prize winner Toni Morrison.

Unfortunately, and you can’t change this—and neither can I—this is how my America begins—not with opportunity—but with chains—and not just then—an aftermath—a legacy, a chronic illness carried in body, spirit, soul, and mind—systemic racism, racial class disparities, political disenfranchisement, violence and terrorism—both from state and rogue citizen. That’s my heritage—triumph and uplift tempered by this—chains linking me back to my father’s first father and my mother’s first mother—who stepped off the boat and may have set foot at the plague house at Sullivan’s (there is some controversy about what and who went where, but the symbolics are all the same) only to await sale not very far from where Husk is today. I am proud to tell you I am an Akan many times over and I am a Mende—a son of rice growers through Sierra Leone leading backwards to the grandeur of Old Mali and beyond that to West African prehistory on the river Niger. I have no names for them—until I die I never will.

When I kneeled—I was told I had to work in the fields, I had to stir the pots, that it was not enough to sit in an armchair and pontificate or grow things as a hobby—these things—you well know—have been done—and often not well—and they don’t serve any of us to any real end. What I endured for their sake—at their command—compares not with five minutes in their lives—and I can honestly say—I would refuse five minutes in their hell. I have it easy. But the hard work taught me to respect those who do the hard work today—who struggle to keep our culture going, who stress and swear because there seems to be no hope in sight. This is for the ramen-eaters, for the food desert nomads, for the kids who cannot take my journey, for the parent who wants to teach our story and pass it on but doesn’t know how to start, where to begin or what to say. My burden is in some ways heavier than yours—and that’s not your fault, but if you care so deeply for this food and where it comes from—and I know you do, you will help me lift a corner of this burden. I know you already do some of this locally–I want to seek a way to do this on a larger scale.

My greatest sin in the Eater piece—as I was quoted by my mishpocheh Hillary Drixler—was calling the “scene,” out to begin to explore a self-directed path of culinary reparations—for a more open engagement with a Black community that is special, unique and proud. Yes stories of great Black historic chefs are being told, and menus are steeped in history and ingredients are telling stories about the people of the past and your menu supports Southern businesses and there are fledgling discussions on how to increase Black traffic in downtown restaurants and putting more Black cooks and culinarians out into the scene. These are the claims at least…I love David Shield’s dedication and sincerity—but even he admitted to me that my nudge and the nudges of others helped opened the minds of many to greater community engagement. And yet–Charleston has a long way to go before it is a center of culinary justice as well as the scene that you and others have obviously worked hard to put on the map. The frustrating thing is that it could be such a city.

When I last visited Charleston I went with Chef BJ Dennis to a food spot where the owner and her customers gave me an earful. She made it clear that Gullah based establishments were often passed up in favor of traditional white owned restaurants in Charleston and that the local African American community did not always do its part to look after its own. One gentlemen—and they ALL know BJ, made sure to tell him before he left, “Remember what I told you, we are not Lowcountry, WE ARE GULLAH.” Then came the refrain—“to the bone.” There are quiet and hidden currents of differing opinions that won’t be heard in mixed company. This is the way –as we both know–of the South.

The cure is to not lie or obfuscate. The cure is to bear witness, to be real, to be truthful. The way to change our fate is to change the names we give and take, to re-arrange our place, to change our deeds, to pray yes, but also to give back and to cry out. (I thank the Rabbis of antiquity for this formula.) My path is not one of quiet acceptance but of a heritage born of the ring shout, forged in blood, sweat and tears in the slave quarter. This is why I cook.

Your colleagues who critiqued the Eater piece thought my comments were personal—and they were not. I salute you for going to Senegal to learn more–but that’s your job. I was annoyed and confused when certain articles deemed you “the white chef version of Henry Louis Gates Jr.” (of Finding Your Roots fame). I disagree with some of your supporters when they assume that the spotlight put on your search for inspiration and ideas is on an “overgrown path”—when African, African American and Afro-Caribbean and Latino culinarians have been writing about these connections and celebrating them without you—and without any media coverage for quite some time. Pierre Thiam’s Yolele and my Fighting Old Nep pre-dated your trip to Senegal—but nobody lauded us for making the connection—nobody said we were exploring “unchartered territory,” nobody said we were going where nobody had ever thought to go. This trickles down—because people will then ask culinarians of color—“How is what you’re doing different from what Sean Brock is already doing?” See—I’m not pissed off at you because I don’t know if you sanction that or not—it’s just already we are being taxed out of the intellectual real estate that is our inheritance. Gentrification is as much creative and mental as it is physical. That article and the Food and Wine piece that followed it was confusing and problematic for a lot of Black culinarians—but we collectively kept our mouths shuts in the best tradition of wearing the mask.

Nobody hates you–nobody hates Andy or Rick–we just want equal opportunity of agency. There is no reason to assume otherwise.

I do not know why you chose not to introduce me at MAD at the last moment or why I have seen you multiple times since and yet you have not spoken to me. I have eaten your food—and your Mother’s food–supported your restaurant in Nashville, I even reached out to you in 2012 when I was a nothing—a nobody—looking to dialogue with you about a little project I was doing called The Cooking Gene. I never heard back after an initial email exchange brokered by a mutual friend. I saw you make jokes on social media—but I desperately wanted to sit down with Sean Brock—to see if you were my blood, my cousin, my kinsman. I have tried to reach out, and my intentions are to squash these feelings of mistrust I am trying to shake.

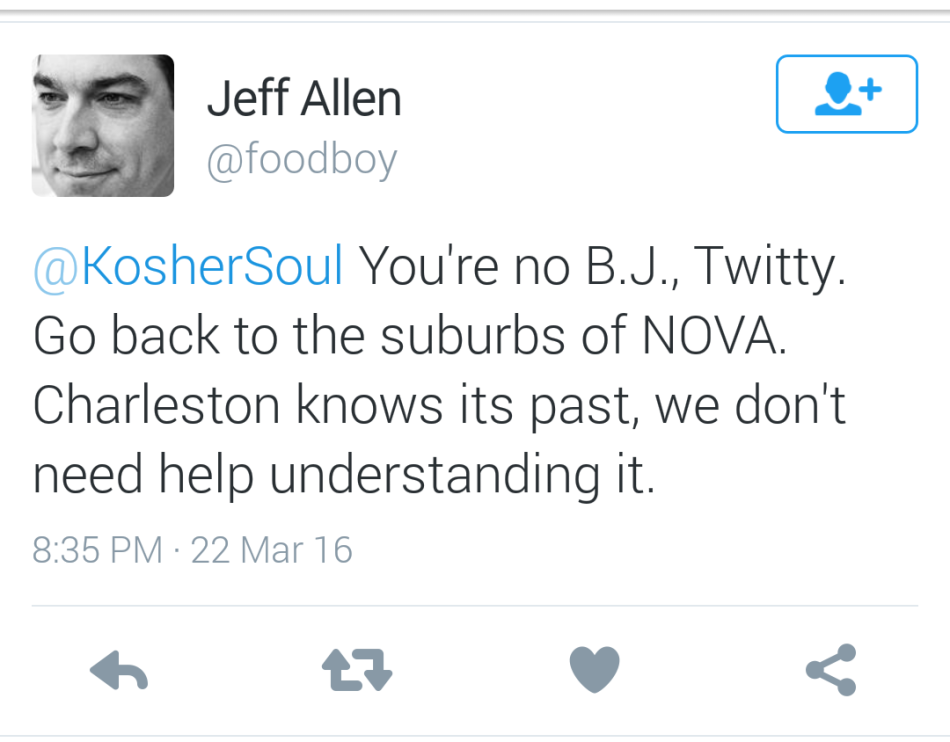

I still do feel the need to reach out but the reaction to my quotes in Hillary Drixler’s Eater piece was swift and harsh—the tone was one of putting me in my place. Despite the fact that Matt Hartman of Durham wrote a very clear, eloquent argument making many of the same points I did—I was singled out for much harsher and direct criticism than was Matt. The wagons were circled. People who I thought knew me well enough to pick up the phone or email me were insinuating that I was nothing short of a culinary carpetbagger a stranger, a fool sent to spread divisive misinformation about a model food scene above the fray of other issues in the world of Southern food—of acknowledging the African presence and agency. I was called out on Twitter—not as Michael Twitty, our colleague—our fellow Southern striver and historian–a man in search of his roots and those of his people and all Southerners–but as @koshersoul the stranger—the disrespectful “comeya”—an invasive voice alongside the soothing peacemaker Chef BJ Dennis. Not cool.

Backs have been turned to me and ears have been closed. Chris Haire said he had no interest in reading Matt Harman’s piece. Where is the reciprocity? Why should one side listen if the other does not? I said “I will not speculate on why Matt Harman has not receved the critique I have.” I didn’t want to even be on record as assuming anything—race—class-sexual orientation—where I live—etc. Chris shot back that I was injecting race. There is it—the new way to diminish our messages—“race baiting,” being “divisive.” We’re tired of this—really tired. B’rer Fox set a good example though didn’t he? Put the tar doll up people will punch before they think. He currently believes I just “half talk out of your ass.” (his words) Oh well. Not everybody has to like you. I’m not in this to avoid critique, but I won’t be called out of my name.

Hanna Raskin and Kinsey Gidick explained what they felt the article’s shortcomings were via the article’s comments section—but in my opinion, they resorted to classic defense mechanisms—progress is slow but its coming…but what’s worse:

(How do you respond to that?)

Then comes the call out—“The interpretation offered up by Michael Twitty is applicable to many places; its possibly even applicable to the Charleston Wine + Food Festival, which Hillary attended. But if she had interviewed a few more Charlestonians who identify as Gullah, she would have discovered that the racial issues plaguing Charleston aren’t rooted in culinary appropriation. The real concern is not giving credit to African American for rice and okra: That’s well underway in better dining rooms. It’s giving them jobs (and critically, promotions.) It’s giving them a warm welcome to restaurants that re now patronized almost exclusively by white people.”

And yet I got this message the same day from one of many Black Charlestonians who reached out:

Anyone who has heard me speak or read my writings knows that’s a straw man if you ever heard of one…Michael Twitty is apparently not interested cooperative economics, diversifying the kitchen, improving opportunities for more brick and mortar Black restaurants and education within his own community—he’s just whining about a boutique rice originally revived to feed ducks—and later re-booted as food for elite humans-just like a 150 years ago. Its not just the ingredients–its stories, messages, marketing–but …Oy, zenug ist zenug.

If I was that simple and boring—I wouldn’t be where I am and all of you know that. Hanna, do not our sages teach to judge the whole of the human favorably (machrio l’chaf zechut)?

Tweets were exchanged—condescension mixed with a flurry of stereotypes—I’m apparently ill-informed, incapable of making and following a logical argument, and at worst a social-media aggressive. It’s not fair to my character, because some of these same people saw me take my time to talk to students in Charleston in a school for behaviorally challenged youth…these are people who have eaten my cooking and watched me sweat on a plantation under a hot sun. These are people who know I have seed collections and have consulted for the best of the best—people who have heard me give the exact same messages at MAD in Copenhagen, in London at the Barbican Theater, at Oxford University and on the stage of TED in Vancouver. It was not that my message had changed, it was that my platform was now here—not there—and that I was not indicting the “scene,” for erasure of the Black presence in the past—it was not sharing the benefits of the now and this is the crux of the Hartman article–and my advocacy.

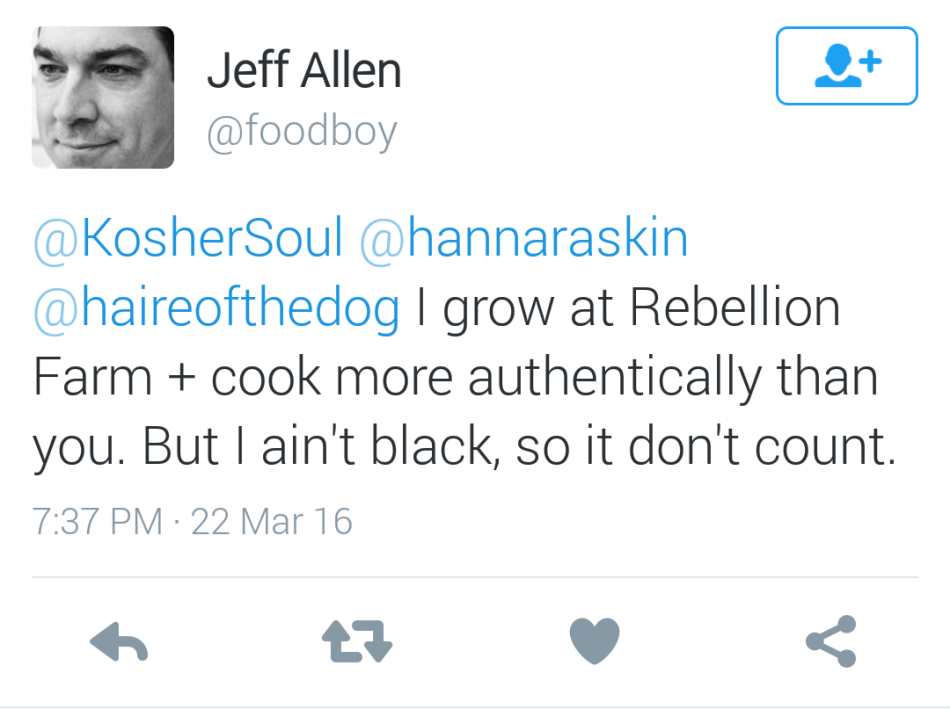

Any of these people—or the whole lot of them could have called me—emailed me—asked to speak privately or put out something that might correct what they saw as an imbalance—but they chose to attempt to muddle my message, marginalize me, and malign by character and intent. Did they feel I did this to their Charleston? No clear answers on that–and no personal outreach. They are still going as I write this. This is extremely disheartening and discouraging. This is not what we need in the current political climate. One tweet from Jeff Allen said “I cook more authentically than you. But I ain’t black, so it don’t count.” Ok so I never said you had to be black to make this food–but if people want to play that old game–they can. The Eater article is clear–I never said that–it explicitly says I don’t harbor that sentiment.

Is this the best we can do in dialogue about what food and identity and meaning are really all about?

Hanna Raskin ‘ s response was “those aren’t the words I would have chosen…” which begs the question, what words were more suitable?

Sean, we, the descendants of these Africans are dying. We are dying of stress and chronic health ailments rooted in diet and quality of food and access. We are in need of economic opportunity and food is such an important gateway for that. We are dying of police bullets and terrorist bullet and many don’t really give a fuck. We are joining our Ancestors faster than we should and as our Rome burns other people’s Rome rises. This is why I’m hot. This is why I cook. This is why I insist on my right of return as the descendant of Charleston’s enslaved and of the rice growers that gave the Lowcountry a story to sell. The South shall rise again, but will we? We need economic development, food justice—and most of all we refuse to be put at the periphery of our narrative when we should remain at its center. I know that you know this is what I’m fighting for sure as BJ and many others have for years.

This isn’t technically your responsibility, but if part of our story is in your hands, so too must be part of a solution.

Sean—if you want to cook sometime let’s do it. If you want to talk sometime let’s do it. We will not agree on everything—nor should we. I have hard questions for you. You have hard questions for me. We are both sincere. But this I know—we are here at this moment on this planet, sharing this heritage for a reason—and we must not waste the opportunity.

Your friend in skillet—your cousin in mind—The Antebellum Chef, Michael W. Twitty, grandson of a great living South Carolinian—Gonze Lee Twitty, founding member, Federation of Southern Cooperatives.

Thanks for this letter, and for your presence in the Eater article. I’m mixed race: Black on one side, Japanese on the other. Culinary appropriation by acclaimed white chefs is a big problem with Asian food (especially when they’re celebrated for “modernizing” or “elevating” it) and I’m disappointed to learn that it’s become a problem for Black food too. It’s especially disappointing to see the particular kinds of rhetoric being used about it being “community property.” Thanks for your righteous and eloquent call outs, and I’m sorry you’ve been the target of all the usual grossness Black people (and other people of color) receive whenever we make those call outs. We have your back on this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you and big big hugs

LikeLike

Eloquent and full of truth, as per usual. Keep speaking out Mr. Twitty!

LikeLike

Their erasure, appropriation and commodification/simplification of Gullah and other African origin cuisine evokes those snide and dishonest rationales for flying the confederate flag — heritage, respect for the past, regional pride, blah, blah, blah. The era of the self-styled Great White Savior is far from over, it just morphs into an endless variety of forms. One is the fantasy of their “discovering” the African roots of Southern food. Just remember, these are folks who still tend to think of Africa as a country and would be hard pressed to distinguish one “source” from another, let alone do informed, sophisticated, and nuanced research such as yours.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Even more than your clarity of argument, your generosity of spirit is truly inspiring and edifying. I wish you well at every step in your vital work, and hope somehow the stars will align for you to visit my students and members of the local community in Florence, SC, soon.

LikeLike

Florence is just up the train line!

LikeLike

this. ❤

LikeLike

You are part Mungo,we as a family “the Mungo’s in Detroit” begs no one for friendships,we will help you, but you must promise us you won’t forgive. I just read what you wrote it’s Beatiful, but never ask for friendships twice.

LikeLike

my family arrived in charleston a long time ago. those who remain there are very proud of themselves. as a (i don’t know, may 10th generation charlestonian?) i would like to support you in your scholarship and in the surfacing of the gullah infuence on american food. it’s immense, as you know, since black people did all the cooking in charleston for a billion years. as someone who grew up in africa and married into a jewish family, i feel you. mighty real. xoxo

LikeLiked by 1 person

i’ve now read the whole correspondence. foodboy is ignorant of you and gullah, and that carpet bagger stuff is 165-year-old code. as i’m sure you know. i wouldn’t hold sean brock responsible for all of foodboy’s sins quite yet; i would hold journalists like the bon appetit chick responsible for fangirl puff pieces, and also bourdain. he loves his ahole chef buddies, and he needs to be instructed on why it’s not news when a white boy does it. bourdain is all about anti-ethical outlaw food; this is a problem for which he should certainly be held accountable.

to say that you, as a gullah, are a carpet bagger, is truly painful even to me who has no dog in this fight. he owes us all an apology.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The whole tone of the retorts from the “white culinarati” stinks of accusations of reverse racism (e.g., “I ain’t black so it don’t count”–REALLY?) As a white person who got schooled on white privilege at a very early age (integration in Northern Virginia, 1966–went from being one white girl in a class of 28 other white kids and one lone black child, to being one of three white kids in a class of 29, the rest of whom were black), I can say that most white people truly don’t understand the concept of privilege nor how much their own attitudes and belief systems are inextricably entwined with all that privilege entails. I am not certain what can be done to rip the blinders from white eyes. It’s not easy to see something you don’t believe exists, even if it’s right in front of you. It will take you finding white allies who can carry your water (and many of them, sadly) before some will even begin to consider that they could have a social responsibility with regard to appropriation and promotion of Gullah cuisine. I applaud your efforts to call out and highlight the behaviors, and appreciate how difficult and important a job this is.

LikeLike

Jeff Allen’s tweets are quite repugnant, especially the one claiming he had lived in a southern town where ‘whites and blacks were equally divided by Jim Crowe’.

This is breathtaking in its ignorance. I’m sure he wouldn’t have swapped his place with that of any of his town’s black citizens. Despite their ‘equal’ suffering.

Sorry, gonna have to say it, the man is a blinkered asshole, prinked with white privilege.

More power to your elbow, Mr Twitty

LikeLike

G_d bless you and your relations. You are a wonderful Jew and human being. Keep on keeping on. You have no other choice in the face of these naysayers. I would use another word but my mother raised me right. Never knew my father.

LikeLike

Pingback: Collards with coconut and peanut butter | Optional Kitchen

Thank you SO much. As a Thai-American, I’ve had my eye on a certain chef, trying to unpack all the violence culinary appropriation does to the the Thai-American psyche.

“Nobody hates you–nobody hates Andy or Rick–we just want equal opportunity of agency. There is no reason to assume otherwise.”

LikeLike

Pingback: Who Owns Southern Food?

Pingback: Michael Twitty Addresses Racial Inequality in the Southern Kitchen | MUNCHIES

Pingback: Who Owns Southern Food? - IMDiversity

Pingback: Michael Twitty on the Hidden Racism in 'Southern' Cooking - Fortune

Pingback: Vote for Afroculinaria for the Saveur Blog Awards 2016! | Afroculinaria

I’m stunned at the response you received, recognize it, but still that it was stated so bluntly by Allen and others is part of the overall disturbance of this political season. One reason to increase knowledge and storytelling is that no one receives such a tweet, telling them they don’t belong. Isn’t that eerily similar to MLK being told he didn’t belong in Birmingham, Alabama?

LikeLike

Pingback: Gullah Cuisine: An Argument And History About Who’s in The Kitchen With A Chicken Bog. – Empires, Cannibals, and Magic Fish Bones

Pingback: Vote for Afroculinaria for the Saveur Blog Awards 2016!

I just read your open letter, and then read that entire Eater.com article. I am ABSOLUTELY FLABBERGASTED that people had ANYTHING to argue with about the facts and points of logic you contributed to the article. I wholeheartedly agree with you here. This is a fantastic article, and I hope you don’t mind if I share it on my social media accounts (even though it is from March) (BECAUSE I AM JUST NOW READING!). What you are saying is SO IMPORTANT for people to hear, even if they react (excessively) poorly. I just want to thank you for this and all of your writing.

LikeLike

Please do!

LikeLike

Pingback: Why You Should Care About the Bon Appetit Pho Uproar - Paste Magazine - ThaiSala

I’m a gay writer on HIV prevention who has had a similar experience of institutional players ‘circling the wagons’ while outriders take pot-shots. I really feel the grief and the anger and the dignity in this post. Through it, I discovered the blog and I’ve been reading all afternoon. More power to your arm.

LikeLike

Thank you brother!

LikeLike

Mat Rodriguez is a friend of mine 🙂

LikeLike

He is a lovely man 😊 I think about to 2004 when we couldn’t even get the gay mags interested in HIV — now it’s part of Mat’s beat at a mainstream publication, and he covers it so thoughtfully. We’ve come so far.

LikeLike

Pingback: 2016 Saveur Blog Awards Recap - The Copper Kitchen

Pingback: Go Read Afroculinaria – Chad Fred Lott

Hi Michael,

Just discovered you and your work from the okra soup you made on 18th century cooking. As someone who is an obsessive historian, I of course highly appreciate the work you have done and the efforts you have made to truly understand historical food preparation. Cooking the same ingredients with a bunch of extra salt in a kitchen cleaned by your numerous staff is simply not the same. Food is so chemically complex and traditional preparations often end up imparting unique qualities.

As a Vietnamese citizen of the US, I am completely on your side of the issue. Frankly, it’s ridiculous what privileged citizens (white or not) are concerned with–trends and social relevance, what’s cool that week, and what’s cool next week. It’s a disgusting form of competition that has evolved out of a societal shaming of traditional wealth-flaunting. Now, the 1% compete with each other to see who can me more of a social justice warrior. But you and I know that these people will never, ever, ever understand what it was like to grow up as a minority in a society that you simply just can’t see as truly yours. They don’t understand the traditions and they try to make up for it with money, marketing, and plating. They read third hand sources and consider themselves highly educated, but it is essential to remember that teachers are armatures of people who once actually “did.”

I don’t like using buzzwords like cultural appropriation, but the reality is that urban white people are always looking to compete with each other (why they moved to the city in the first place) and if you tone down the flavors and up the salt, you can convince people your food is unique, authentic, and worst of all, “elevated.” This is primarily because humans want to brag about themselves, so since they find bastardized dishes palatable compared to their frozen pizzas, they can go brag about it. An actual meal consisting of something like fish heads or blood cakes? Haha nope. When the country discovered banh mi I just simply was confused. Here is a $2 sandwich being made worse in hipster eateries in an attempt to “elevate” it, when it really just comes from a lack of understanding. I overhear white people talk to the local ramen shop owner about how their family loves making pho, but for some reason even with the best organic produce, they just can’t get it to taste as good. NEWS FLASH YOU FORGOT THE MSG. People are hilariously uneducated on our cultures and our flavor profiles and when I go to new uber-popular modern Vietnamese restaurants, the food is seriously disgusting every single time. And I have been to some of the most popular, like the slanted door. Simply gross. I’m ok being real here because I have no reputation on the line. These fusion restaurants just dump in a bunch of extra salt and make the sauces really strong, it’s simply no longer palatable to someone who actually grew up with authentic Vietnamese cuisine prepared by their native grandmothers. It just makes it insulting when you see these restaurants get lauded by uneducated white people, like your authentic self and heritage is worthless. That the true flavor profiles of your cuisine are somehow “not gourmet” or Michelin-star worthy. That success only comes from white-washing. I understand how privileged people feel, that they are only just trying to eat something tasty, but ultimately the reason they refuse to accept what you say is because ultimately there is no direct response to this. You got called out by someone you could never fairly argue with, so you start coming up with bullshit. It’s simply how these people were taught to live in elementary school. It feels like your life potential has been stolen from you when you see others getting massive amounts of credit simply for doing something you have done your whole life. Some idiot who decided they wanted to travel to your home country at the age of 35 to “discover the roots,” sorry but that is so fucking stupid. Some serious Christopher Columbus syndrome. A 3 week trip will teach some nerd NOTHING compared to being raised in a culture and to make any claims as towards the authenticity of what is necessarily inauthentic cooking is a slap in the face. I love that you are making the tough effort to tackle this issue! Thank you so much! There is no real response these liars can give, because they know they are frauds. They are smart enough to realize what style of restaurant they can sell to their uneducated customers and simply desire such a reputation to drive their sales.

Funnily enough, I am planning a trip to Charleston with my girlfriend. I will definitely boycott Jeff Allen’s establishments because what he tweeted is what prompted me to comment. Simply disgusting, despicable behavior. What a little shit. Unfortunately I want to punch him. Saying “I ain’t black, so it don’t count” not only is grammatically incorrect (I find that people who add unnecessary commas are usually narcissistic assholes, in their puny minds they are pausing for dramatic effect hahaha) but it also exposes his deep-seeded insecurity. To abandon the food he grew up with and knows best in favor of another people’s cuisine only shows his psychological feeling of inadequacy and an immature need to constantly find new things as a salve to his emotional hysteria. Haha I guess I would say you can take pride that white people have become such nerds that they desperately want to be black in an effort to exude even a modicum of masculinity, but you and I both know it doesn’t really feel very good at all.

It’s an unfortunate situation because we are certainly not trying to prevent anyone from cooking outside of their culture. We’re not even attacking such chefs directly, but rather the inverse social effects of the way the media uses excessive positivity to get clicks. If you make something ok seem amazing, people will want to check out your article. This isn’t so much an attack on chefs so much as it is on the idiocy and lack of education of the media whose job it is to influence (and manipulate) minds. Nobody should brag how authentic their cooking is. And I think the palpable issue in the end is that while the media uses its clever tools and smooth user experience design to bring customers into these pretty spaces, the whole community would be better off if these people had instead visited a local restaurant run by those whose heritage they have actually inherited, bringing money into poorer communities so they too may have a chance to afford a fancy, instagrammable interior as well. The unfortunate fact of the matter is that some products sell precisely because of their high price tag, tricking customers into thinking it must be worth it or better than something cheaper. Often this may be true, but when it comes to ethnic cuisine, it simply isn’t. Our people developed poor and with whatever they had in the area and developed traditions of cuisine based on the cheap ingredients they had available to them. And now all of a sudden local farm-to-table is a food trend? More like how most of the third world has always eaten. Local food and the deeper and more developed flavors it produces is so friggin obvious to us. I honestly think we should develop culinary traditions this way, based on what we have available. And bored-ass white people getting avocados and mangos shipped to the them from South America in the middle of winter are not “becoming more cultured,” they are trashing the ecosystem that our food directly comes from. This current obsession with foreign food is tricking people into thinking they are progressive good people when in fact, it’s highly dishonest and potentially detrimental to the environment (as well as lacking good flavor!).

Treating us as some sort of mystical pho-making wizards that you earned tutelage under is a modern version of the noble savage and in the end, actually offensive. I think one of the main issues and reasons white people reacted so strongly to your piece is because they are in their mind thinking they are being really nice and progressive. I know it must suck to be a normal white person and just get called out like this, but honestly the nail that sticks out gets hammered in. Don’t beat your chest too hard about being best friends with ethnic people because really, all you’re doing is objectifying us and reminding us of what we never had in the first place. The treatment and respect as a true equal.

Thanks for fighting for true understanding of tradition, I seriously appreciate watching you cook in historically authentic ways because it is so damn fascinating to me how hard a simple life was in those times. It really makes me appreciate the generations of learning and development that has led to the prepared meals we take for granted every day. The world is in a tough place right now. The liberals became incredibly full of themselves when they really were doing very little to save the world, and what’s worse is their arrogance pissed of the conservatives who are now coming out of the woodwork and evangelizing their ideals in a misguided effort to stem the negative societal side effects of a population of intellectual narcissists. Folks like you remind me that not all is lost, that there still are those fighting the good fight–and for that I am incredibly grateful. I look forward to your book release.

LikeLike

Jeff and I made up face to face but I can’t tell you how much I appreciate your reading of this piece. I’ve always said that until others can see what we see and feel, it doesn’t hold the same weight.

LikeLike

Pingback: Saveur’s 2016 Best Gourmet Food Blog Award Winners – Part 2 – The Happy Eggplant Gourmet Food & Kitchen Shoppe

I found you through the “Food of the Enslaved” series. I’m familiar a bit with social justice, but before serrendipitously running across your work, I’ve never heard of food justice.

And you opened my eyes, and I’m moved by your thoughtfulness and passion, and find you incredibly engaging.

But on the other hand, as a white, fairly affluent southerner who enjoys cooking, dining, and trying to experiment and replicate (and dare I say “suit to my own tastes” or whatever) dishes that I didn’t grow up with and which my mother and grandmother DIDN’T make (tonight it was something similar to Pad Thai; yesterday was Texas red chili; last week was Cuban pork shoulder; this weekend was gumbo; you get the idea), I’m not sure what to do with this information. My mother was a middling home cook who came of age in white America where jello salad was a thing that got served unironically to people who you allegedly loved. I didn’t exactly inherit some great culinary tradition.

Food-wise, I was fortunate to have grown up in a diverse town, and to have had black and brown friends who weren’t saddled with the same type of jello abuse at their own homes, and whose families graciously allowed me to dine at their tables. So I was exposed to how things were different at different families’ tables. But it’s not like I have any cultural claim to any of that. And up until recently, I didn’t think it was something like a prerequisite.

For me, I cook because 1.) I like to; and 2.) because, well, my family’s got to eat. I like cooking with ingredients I’ve never used before and finding methods and recipes that sound tasty. And if I’m understanding, that’s something like privilege — cooking a certain way and with certain ingredients weren’t “options” or some fun new culinary diversion for oppressed people; they ate what they ate because that’s what there was and that’s how they learned its preparation. And the simple realization that “hey, this is pretty good to me” isn’t — I dunno — respectful enough.

But I still don’t know what to do with this information. I love me some Texanized gumbo and faux Pad Thai. When is it cultural appropriation and when is it simply a quick, weekday meal that I wanna knock out (and fuck it, I can sub 1 part ketchup and 1 part Sriracha for tamarind paste because that’s what I have in the fridge right now, and free-range chicken thighs for tofu, and ixnay on the tiny dried shrimp because, well, I don’t like them, they stink a little bit, and their tiny eyes freak me out)?

I guess the personal is the political, but I am still unclear about the role the white home chef (who mostly gets recipes and ideas from Serious Eats, chefsteps, Chef John, and trying to reverse engineer ethnic food that I enjoyed eating that is no way my own) plays in making food more just.

But I’m interested in your work.

LikeLike

Pingback: A Black Food Historian Explores His Bittersweet Connection To Robert E. Lee - Dekalb Chronicle

Pingback: A Chocoholic’s Guide to Natural Chocolate’s History – Dinner for Three

I grabbed my coffee as you said and I read this word for word, through and through. This was beautifully stated and I really do hope that you and Sean Brock get to sit down and talk. I think that together, y’all can conquer anything that you put your minds too, especially with a mindset like that. As a student, I have watched Cooked with Sean Brock’s southern food and what he is trying to do is inspiring. And you, Michael Twitty… Listening to Black Corn was eye opening so please keep up the great work! I look forward to your future work as it gives me a new light when it comes to living in the south. You have made me see things that I would have other wise looked right over. Thank you for helping me appreciate the history of the south so much more than I could have ever thought. Without you, I still would be pretty naive on how certain foods came to be or just the culture in general. Again, amazing work!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 2 people